Clash of the Titans!

Not too long ago, Albert Derolez tackled the notion of palaeography as an art, particularly disparaging what Bischoff lauded, that is palaeography as the ‘art of seeing and comprehending’, while defending that which Bischoff feared, namely the ‘art of measurement’. The ‘traditional’ method, as Derolez calls it colloquially, espoused by James, Bischoff and Gasparri among others, holds that the subject cannot be taught, but through apprenticeship, the long handling of books, practice and individual experience, one may eventually develop ‘the palaeographer’s eye’. This is not so much learning as initiation. As Derolez said with a laugh when I pressed him on the subject during a coffee break, ‘They want it to be hard!’.

Whether this viewpoint is predominant (and correct) or not, depends on your perspective. There is of course an undeniable appeal in the promise to open secrets known to a very few, to be part of a select group that has the experience to make authoritative assessments on the date and origin of seemingly illegible writing. In fact, something of this enticement lurks behind many medievalists’ interest in the Middle Ages, the allure of knowing arcana that require specific training, whether it be Verner’s law, the liturgy or the ability to read cursive hands.

Yet as alluring as this appeal is to those of us who move on to related academic fields, the qualifications for entry seem prohibitive for those who want some familiarity with the subject, but have no plans of professional pursuit. Whereas Derolez suggests that the qualitative assessments of connoisseurs (in contrast to the quantitative methods that he prefers) have contributed to the ‘crisis of palaeography’, I’d like to add that the prohibitive barrier to entry does not serve the subject well in the present academic zeitgeist (be it good or bad, it’s what we are faced with). With that in mind, a couple of ideas.

First, open the doors. Last spring, a colleague proposed and set up a mini Introduction to Palaeography. It ran two weeks in which there were six lectures (2 by Åslaug Ommundsen, who set the course up, 2 by Odd Einar Haugen and 2 from me). No previous knowledge of Latin, Old Norse or Old English was required. And the essentially 1/3 credit course was marked pass/fail on the basis of three assignments (basically, students could choose to identify and describe some early scripts, reassemble a fragment and discuss its writing, inventory the alphabets of hands writing both Latin and English, and/or expand abbreviations from a modern Norwegian recipe to create a system).

She got over 40 students (just over 50 registered, but a few always drop) and the course got written up in the UiB paper. We know the number was high for several secondary reasons such as its novelty; a pass/fail course to get a few points that can round out a degree probably drew some in as well. And of course these students won’t be admitted to archives based on this short introduction. But they did get a chance to see a few fragments and incunabula in the special collections of the library, and an opportunity to see if these were interests they want to develop further. This spring a similar course will run for codicology; to date 15 students are registered, which may not sound extraordinary in itself but compares well with enrollment in Latin and Old Norse at UiB.

Second, use other courses to sneak some palaeography in. Like a number of universities, Bergen has a growing ‘Digital Humanities’ field (with many engaging and active people). And seeing that many books on contemporary on-line media, such as this one on blogging, frequently give overviews of textual history (oral to written, manuscript to print, published to recorded and filmed, the electronic era, you get the picture), a course along similar lines, a history of textual/reading/writing technologies, say, should appeal to digitally minded colleagues who might be willing to collaborate. Here, I don’t have the experience to back it up, but some initial inquiries and discussions are promising. I’ve got a good ‘Yeah, that would be good for a students’ as a preliminary invitation to pursue the idea further.

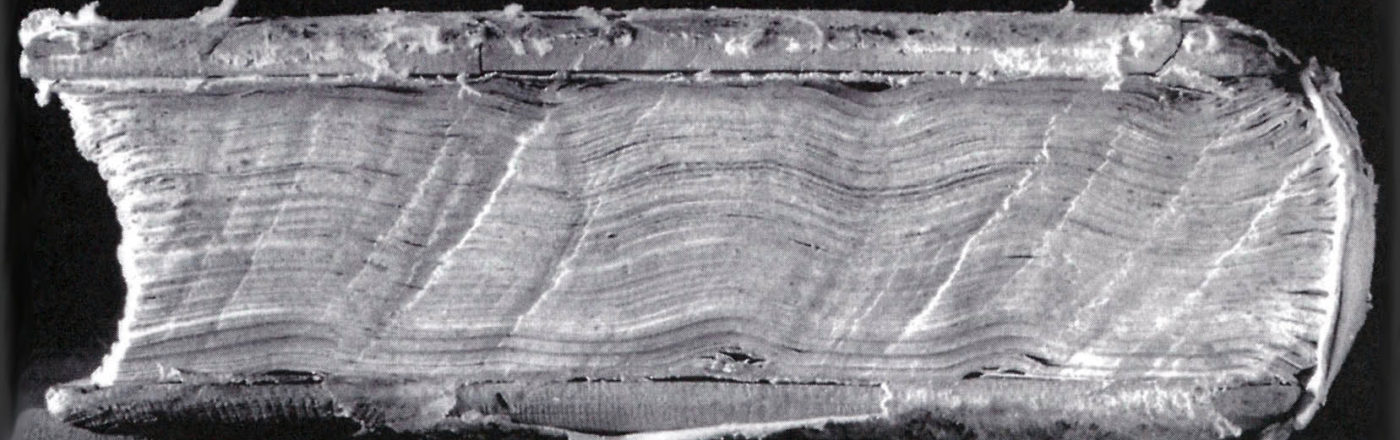

Such a course wouldn’t be palaeography in, of and by itself, but even for those who show no further interest, it will produce some familiarity with and ideas of other types of work. And for others it might open up new possibilities, because the palaeographer of the future looks more like a person (pictured here) with degrees in Classics, English and computer engineering than the Benedictine of the seventeenth century credited with founding its study.

Whether its a crisis, the end times or just a bump in the road, the field changes. To those who say ‘no-duh’, I still would like to see more active and creative engagement. To those who will say ‘no way’, enjoy the view while it lasts.