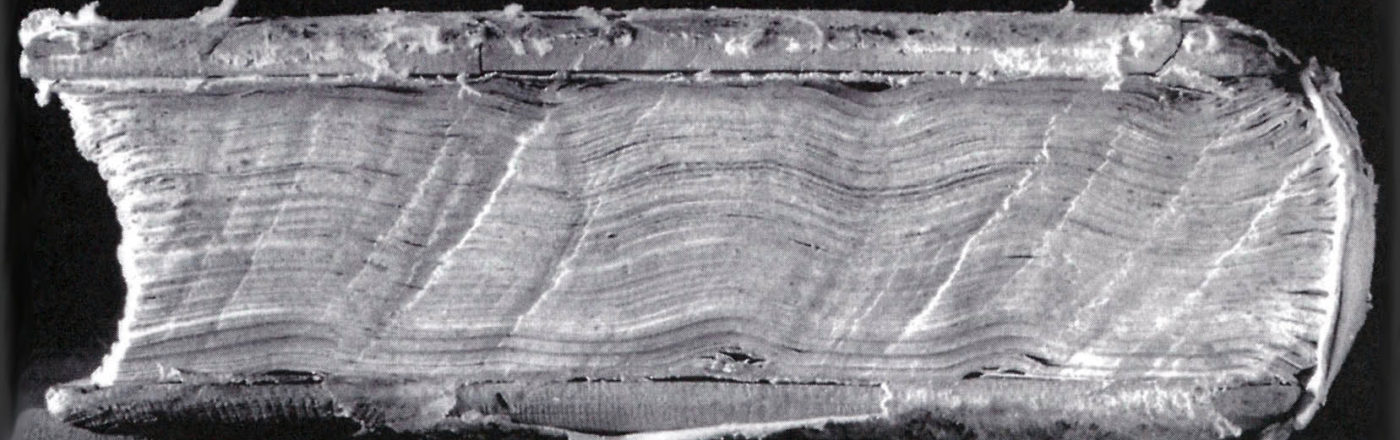

A Carolingian binding

References to the price and labour involved in producing early medieval books in Western Europe are hard to come by. However, thanks to Helmut Gneuss’s reconstruction of a scribal comment (aka colophon) now lost (but transcribed by a modern cataloguer before the loss of the manuscript), we have a unique reference to the price of a book in early English material (it may well be the earliest reference of its sort in western Europe).*

It reads (as reconstructed):

Äeos Boc wæs geal gewriten on feower

Wyken and kostede þreo and fifti syllinges

This whole book was written in four weeks and cost fifty-three shillings.

The hand-written catalogue description of this lost manuscript (probably written very roughly around 1100) has not been printed but Gneuss relates that it was 21×15 cm and contained a Latin psalter and canticles over 152 folios (with another seven folios added later). However, the statement itself gives no indication as to whether the cost involved the materials or only the labour.

Nonetheless, it seems worth gathering some (provisional) points of comparison (about which corrections are welcome; I am especially uncertain about conversion rates and the like). In 900 in England, a sheep was valued at 5 pence (?or about 1 shilling) and a pig at 10 pence (?or about 2 shillings).**

In the medieval Islamic world, an ordinary book could cost 10 silver dirhams (?7 dinars by weight) and a fine one 100 dirhams (?70 dinars). The annual income necessary to support a middle-class family was around 24 dinars. The library in Cairo under al-Hakim (r. 996-1020) had an annual budget of 207 dinars per year, 90 of which went to paper for copyists and 48 for the librarian’s salary. The keeper of the supplies and the repairer of books each earned 12 dinars.***

In Byzantium, annotations from around 900 in the books of Arethas, Archbishop of Caesarea, value his copy of Plato at 21 nomismata (6 8 [Thanks to Marilena Maniaci for the correction!) for the parchment) and Euclid at 14 nomismata (perhaps not including the parchment). Manual workers in Byzantium were paid 6 to 10 nomismata per year. Those in the civil service appear to have earned about 72 nomismata per year at the lower end of the scale (the average perhaps in the hundreds).****

This only represents the early end, which interests me in considering a/the development and/or shift from sacred book to commodity. More examples and comparanda kindly solicited.

—————-

* Helmut Gneuss, “More Old English from Manuscripts” in Intertexts: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Culture presented to Paul E. Szarmach ((Tempe, AZ: ACMRS in collaboration with Brepols, 2008), pp. 411-421 at p. 419.

** from VI Æthelstan, see s.v. coinage in Lapidge et al., The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999).

*** from Jonathan Bloom, Paper before Print The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2001), pp. 117 and 121.

**** from Robin Cormack, Byzantine Art (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000), p. 132.