Recently, a colleague was discussing the procurement of personal preachers in particular places during the later Middle Ages, which piqued my interest. So I asked about the arrangement, that is whether these people were paid or if the relationship was based on mutual ties and benefit. When in turn I was asked why this might matter, I ventured that if we are interested in the social relations between the parties the nature of the exchange matters. This impressed upon me that the importance of book prices might not be as self-evident as they seem to me.

Recently, a colleague was discussing the procurement of personal preachers in particular places during the later Middle Ages, which piqued my interest. So I asked about the arrangement, that is whether these people were paid or if the relationship was based on mutual ties and benefit. When in turn I was asked why this might matter, I ventured that if we are interested in the social relations between the parties the nature of the exchange matters. This impressed upon me that the importance of book prices might not be as self-evident as they seem to me.

If the book is regarded as a sacred object, a reader’s or the audience’s relationship to its authority is fundamentally different from one in which the book is seen as a bought-and-sold commodity. In other words, the attitude towards and indeed the access (or lack thereof) to the material embodiment of the text plays an important role in one’s reading of the text (and/or the authority through which interpretation is transmitted).

In charting the early iconography of the Christian book, namely the shift in depictions whereby the once open book becomes a closed and ornamented object, Armando Petrucci argues for an ‘ideological process of sacralization’.* And in turn sees connected to this development a ‘conception that saw writing not as in the service of reading but as an end in itself’, divorcing the practice of writing from that of reading, enabling scribes to write with little concern or regard for the needs of reading or readers.** (While I admittedly have a hard time getting my head around the notion of writing as an end in itself, this point of view does help explain some of the errors that any reader of medieval manuscripts comes across; you can’t help but think when looking at a text that clearly was corrected either by the initial scribe or subsequent users, ‘Why didn’t they fix That! Surely, everybody noticed that Gedeon shouldn’t be spelled Zedeon?!’). If this accurately describes written culture in the very early Middle Ages, a shift whereby one might ‘buy’ what was a sacred object, written as an end unto itself, strikes me as a rather important and dramatic process.

In addition to issues of access to texts and authority in interpretation, the shift from sacred object to commodity is also an important part of economic history. In discussing Dobb’s Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946), Stephan Epstein noted, “Two critical questions were never posed: First, why did the transition to capitalism occur originally in western Europe, even though parts of Asia were previously economically more advanced?”*** There seems to be a parallel question asked for the history of the book. Why did printing develop in western Europe when other societies had the technological tools for the same development and in some cases were (or had been) more ‘advanced’ both in the economies of book production and the technologies of print? Interestingly, it is often suggested that it was Gutenburg’s (and by extension western Europe’s) business sense, or search for profit that engendered the desire and drive to create the press, and that the book market that had developed prior in the Middle Ages enabled its subsequent success.

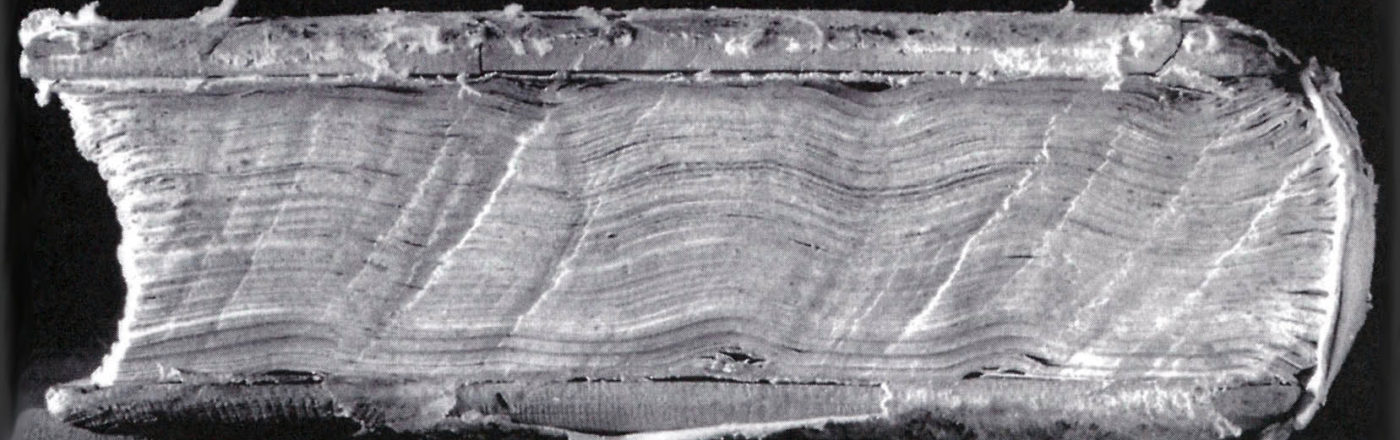

Seeing that we are witnessing pretty radical re-assessments of the ‘stasis’ of the medieval economic world, including the write up of a paper that posits dramatically higher income in late medieval England than previously imagined, it seems that we might revisit the knowledge economy of the Middle Ages, keeping in mind the extensive networks that book production required and created well beyond the scriptorium. For the Bury St Edmunds bible (c. 1135) for example some parchment was sourced (or at least a desire was expressed for parchment sourced) from Scotland, testimony to the possibilities for rather far reaching trade at a rather early date.**** The regional differences, or the uneven distribution, in the development of a/the book trade (along with other social considerations such as urbanization et al) might serve as a useful way of gauging differing points of entry into differing realizations of modernities.———————–

* ‘The Christian conception of the book in the sixth and seventh centuries’ in Writers and readers in

medieval Italy. Studies in the history of written culture, ed. and trans. by C.M. Radding (New Haven, 1995), 29. Originally published as: ‘La concezione cristiana del libro’, Studi medievali, third series, 14 (1973),

961–84.

** ‘Christian conception’, 32–33; See also, Petrucci’s ‘Reading in the Middle Ages’, in Writers and readers. Originally published as: ‘Lire au Moyen Age’, Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome, 96

(1984), 603–16.

*** in “Rodney Hilton, Marxism and the Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism, Past & Present, Supplement (Volume 2) (2007), pp. 248-269 at 250.

**** Rodney Thomson, The Bury Bible (Woodbridge, 2001), pp. 25-26.

Pingback: Scribal Labor, Ancient Edition | Nugatorius scriptor