One of the most interesting (admittedly, to me) characteristics of manuscript culture, that is a literate culture distinct from print, is the handwritten transmission of texts, a phenomenon that demands a better understanding of the mechanics of copying. In short, how does the individual read while s/he is writing and/or write while s/he is reading. And how does this practice affect the way that texts shift, move and change.

At the heart of the copying process is the scribe, whose education, habits and working practices vary according to time, place and any number of considerations. Nonetheless, I think that we might be able to talk about some general principles that apply to copying as a practice. At least I would like be able to talk about generalities about reading and writing that can be applied to the specific mechanics of copying.

One attractive principle is the notion of ‘transfer units’ as described in Malcolm Parkes’s Their Hands Before Our Eyes, A Closer Look at Scribes, a significantly revised and augmented book based on the Lyell lectures at Oxford in 1999.

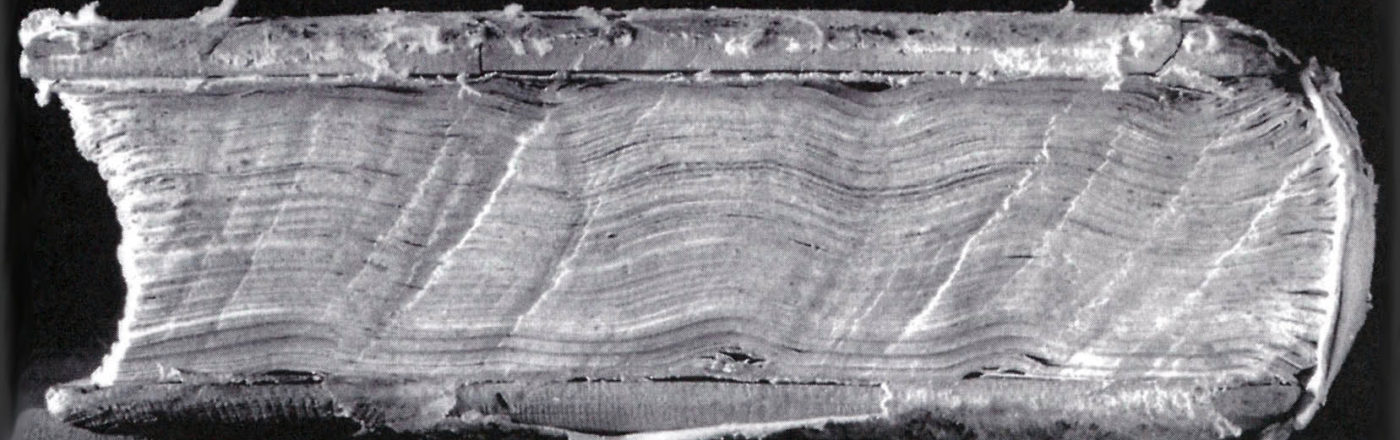

When a scribe copied a text he had to divide his attentions between exemplar and copy, and the degree of concentration required is reflected in the frequency of the transition from one to the other. The transitions may often be detected from minor discrepancies in the spacing or the alignment of the handwriting on the pages of the copy…(In the example under discussion, a scribe, Hrannigil) reproduced the scriptio continua of the exemplar for certain groups of words, which indicate the amount of text he retained in his memory when transferring his attention from the exemplar of a difficult text to his copy. These ‘transfer units’ can be seen in the copy…(and) are also ‘conceptual’ units. (63-64)

In this description is the promise (not invariably, but in some cases) of being able to discern — almost as if viewing an instant replay — the scribe’s reading and writing by looking at the ‘transfer units’ in his/her copy. In turn, we might be able to see when mistakes were more likely, what kind of sense units produced what kind of copying anomalies and so forth.

Parkes’s example is based on a ninth-century copy (by Hranngil a scribe at Rheims) of a sixth-century Italian examplar. Obviously, the cases in which we know the specific manuscript from which a scribe copied are pretty few and far between, which makes the case so compelling and tantalizing. But I honestly wonder if what we hope to see, namely evidence of transfer and conceptual units, is indeed what the page reveals. In considering the word “inintellegibile” in Hranngil’s copy, Parkes states “Misalignment after ‘sed quod’…reveals that Hrannigil hesitated over the word ‘inintellegibile’, where he appears to have checked the exemplar again to ensure he head not misread the word, before writing the second syllable.”

But, when I look again I notice that the foot of the second stroke of the first ‘n’ is in fact already higher than the bottom of the first stroke of that same letter. In other words, the misalignment begins with the finish of the first syllable. Perhaps, this suggests that the scribe began questioning whether to write ‘inin…’ or ‘in..’ as ‘n’ was being finished. Or, perhaps the irregularity (in strokes’ relation to the baseline) in this letter, and throughout the word, is characteristic of Hranngil’s practice in general, regardless of the sense units that were used to transfer text. The more I look the less certain I feel about either possibility. I would certainly like to see people copy under observed circumstances to get a better feel for the process (if only to better conceptualize medieval practice, not to recreate it). I’ve made some tentative steps in this direction…please stay tuned.

But, when I look again I notice that the foot of the second stroke of the first ‘n’ is in fact already higher than the bottom of the first stroke of that same letter. In other words, the misalignment begins with the finish of the first syllable. Perhaps, this suggests that the scribe began questioning whether to write ‘inin…’ or ‘in..’ as ‘n’ was being finished. Or, perhaps the irregularity (in strokes’ relation to the baseline) in this letter, and throughout the word, is characteristic of Hranngil’s practice in general, regardless of the sense units that were used to transfer text. The more I look the less certain I feel about either possibility. I would certainly like to see people copy under observed circumstances to get a better feel for the process (if only to better conceptualize medieval practice, not to recreate it). I’ve made some tentative steps in this direction…please stay tuned.

Pingback: (Imagining) How Scribes Worked #2 | Nugatorius scriptor