This article from the Washington Monthly raises many questions, surely some concerns, and even perhaps in some quarters optimism. Can we have college for 99 bucks a month? The author, Kevin Carey, followed up with an appearance on NPR’s Talk of the Nation in a segment entitled Getting an education on the internet.

The entire piece explores the future of higher-ed in light of on-line learning. The prognostication:

The accreditation wall will crumble, as most artificial barriers do. All it takes is for one generation of college students to see online courses as no more or less legitimate than any other—and a whole lot cheaper in the bargain—for the consensus of consumer taste to rapidly change. The odds of this happening quickly are greatly enhanced by the endless spiral of steep annual tuition hikes, which are forcing more students to go deep into debt to pay for college while driving low-income students out altogether…Which means the day is coming—sooner than many people think—when a great deal of money is going to abruptly melt out of the higher education system, just as it has in scores of other industries that traffic in information that is now far cheaper and more easily accessible than it has ever been before.

To date, most of the success in outsourcing higher education to third-party online enterprises has come in introductory courses, those in which information-feeding, or perhaps learning the basics before moving on and arguing within the field, is a large part of the course objective. That may give a false sense of security to those who provide upper level critical thinking (a skill that many people looking for 99-dollar credits won’t need). And the conventional wisdom is that famous, elite, wealthy institutions will weather storm, even if doing so means returning to their pasts as social institutions (even more so than they are at present) where members of the same class develop relationships which will serve their careers whatever education they may pick up along the way (as Krugman describes in White Collars Turn Blue). In other words, even those people and places that ‘survive’ will likely be dramatically changed.

I would add that for the accreditation wall to crumble, it will require both a generation of students and employers to see on-line courses as legitimate. Once in place, the education as job-training circuit will be complete. In that world, the humanities look pretty superfluous unless, of course, it fits within a four-year book club for those who have the luxury of some time out.

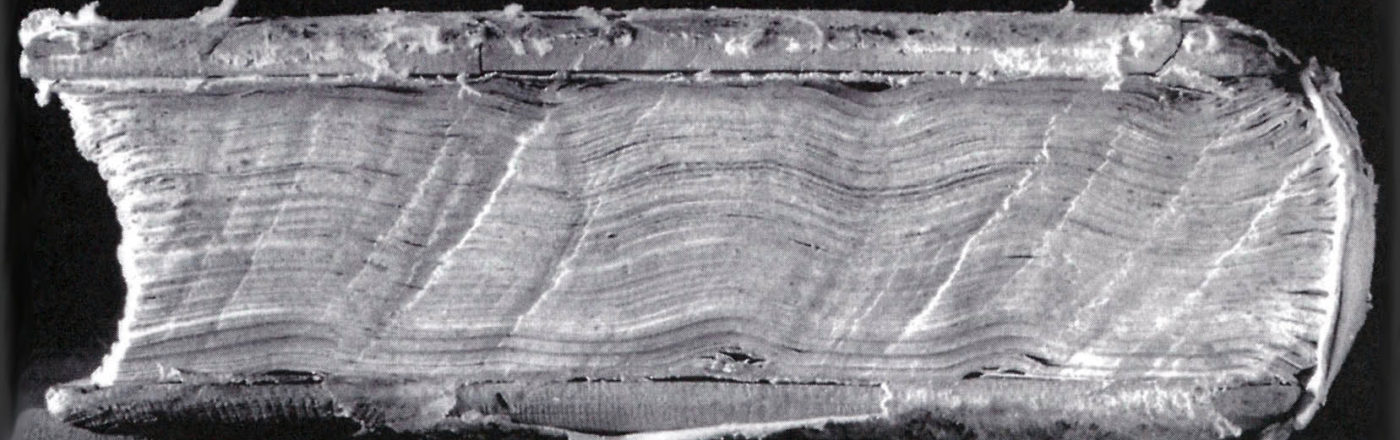

As a medievalist, or one who teaches and researches one of the more obscure branches of the impractical, the negative ramifications may be most pronounced. Already (and perhaps this is perception shaping reality), it seems that a good number of students in Old English, Medieval Latin and palaeography are non-traditional, and more specifically older students returning to the university for a few courses after a career elsewhere. And while ‘pleasure’ is certainly a good reason to take a course, fewer students seem to consider the humanities a viable career or a field that can viably inform any possible career. In this light, it’s not hard to imagine an environment in which teaching becomes more entertainment, ‘delight’ for those who have free time to indulge their curiousity, and less work, in which students demand instruction so that they can pursue the subject further or understand the issues involved so that they might be better informed wherever ‘further’ might lead.

I intend no invocation of a glorified past, no return humanistic golden age, and no call for things as they once were (but never are). In many respects, greater access to more education is a welcome counterpoint to other trends of the past quarter century (in the U.S.) such as increasing income disparity and decreasing social mobility. But how does one individual navigate the flux?